Welcome to the rainforest. But where is all the rain?

By Luke Cooper, President – Friends of the Henty

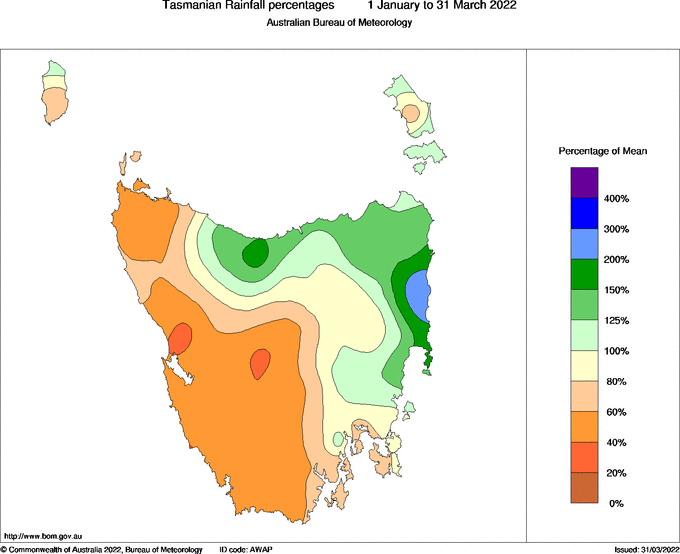

A recent ABC article stated that Tasmania had recorded its driest Summer in 40 years. For those in the North-East of Tasmania this may seem absurd, with parts of North-East Tasmania recording up to double the average from January to March. But on the West Coast of the state, the dry summer was more than apparent. In fact, for many areas on the West Coast, the Summer of 2021-22 was one of the driest ever recorded. In particular, at Lake Margaret Dam, notoriously one of the wettest places in Tasmania, recorded its driest January on record, 48.2mm compared to an average of 215.2mm.

While less clear, it seems that Strahan has recorded its driest January also. In Strahan, there have been a number of different rainfall recording sites over the last 112 years, the main ones being, Regatta Point (1908 – 1948), Vivian Street (1971 to 1991), Andrew Street (2013 to Present), and at the Strahan Airport (1981 to Present). Both the Andrew Street site and the Strahan Airport site recorded the lowest rainfall on record for the month of January, with 13.8mm recorded at Andrew Street, and 16mm recorded at the Strahan Airport. These are compared to the January averages of 70.7mm for Andrew Street and 81.3mm for the Airport. Both of these records are lower than any January rainfall recorded at the Vivian street site between 1971 and 1991 and the Regatta Point site between 1908 and 1948.

What about the unaccounted for period from 1949 to 1970? About 13km South-West of Strahan is the Cape Sorell weather station that has rainfall records dating back to 1899. The driest January on record at Cape Sorell during the 1949 to 1970 period was 27mm in 1954. Unless there was substantial variation in rainfall between Strahan and Cape Sorell between 1949 and 1970, Strahan has recorded its driest January in 112 years of records.

This January at Cape Sorell, while not quite record-breaking, Cape Sorell recorded its second lowest January rainfall on record; 15mm compared to an average of 67.4mm. The lowest January rainfall ever recorded at Cape Sorell was measured just 3 years earlier, at 11.2mm.

It wasn’t just one month though. Strahan and Cape Sorell have recorded below average rainfalls in the months of December, February and March also.

Figure 1: Percentage of mean rainfall over the last 3 months of 2022. Strahan has seen less than 40 percent of its mean rainfall so far in 2022. Source: Bureau of Meteorology.

Figure 2: The past three months have seen Western Tasmania at least 1 degree above average maximum temperature. Source: Bureau of Meteorology.

This Summer on the West Coast is at least partially explained by a La Niña event. But, as the climate continues to change it is possible that sustained periods of hot and dry weather will become a more frequent event. What could be the consequences of a drier West Coast?

Bushfire

The west of the state faced a couple of scary bushfire situations this Summer. One burned very close to properties in Tullah and another within a few kilometres of the Truchanas Huon Pine Reserve, one of the largest remaining stands of mature Huon Pine in the world.

Given the conditions of this Summer the West Coast was relatively lucky. Although if hotter and drier Summers become more common, the West Coast is unlikely to stay lucky for too long. Sections of vegetation on the West Coast are high conservation value rainforest and alpine environments, containing endemic conifer species, including huon pines, king billy pines, and the many species of dwarf pine. Much of this vegetation is fire intolerant, and species such as the endemic conifers are unlikely to survive if bushfire extends into these areas. The Raglan Range was burned in bushfires in 1898, 1934 and 1939. As a result, the vegetation on the range was dramatically changed, and the hundreds of ghostly white King Billy Pine corpses that are visible from the Lyell Highway are a reminder of how vulnerable coniferous trees are to fire.

Figure 3: Dead white King Billy Pines in the distance atop the Raglan Range (Photo by Luke Cooper 2020)

While these conifer species are typically confined to either montane areas or wet rainforest, sustained periods of hot, dry weather and increased average temperatures are likely to make these environments more vulnerable to fire. There is evidence to suggest that trees, such as king billy pine and pencil pine have already been pushed to these ‘fire refugia’ post-colonisation due to changes in fire patterns.

In addition to the threat to vulnerable vegetation, most towns on the West Coast are in very close proximity to forest and are therefore at an increased risk if bushfire becomes a more common occurrence. The bushfire at Tullah this year was a stark reminder of this fact.

Additionally, West Coast towns, particularly Zeehan, are bordered by mature stands of invasive gorse and broom plants, both of which substantially increase fire risk. Gorse and broom are fast growing, have high oil content, and often have many dead branches, providing easily burned material all year round. Unless large scale and long term action is taken to reduce the gorse and broom infestations on the West Coast, the risk posed by these weeds will only increase.

Ginger tree syndrome

The Henty Dunes, a substantial sparsely vegetated mound of sand, sits just east of Ocean Beach and about 10km north of Strahan. Around the perimeter of the dunes grows a subspecies of manna gum endemic to the region, Eucalyptus viminalis subsp. hentyensis. Eucalyptus viminalis is particularly susceptible to a phenomenon known as ‘ginger tree syndrome’. The syndrome sometimes occurs in Eucalyptus after extreme heat events. The bark shrinks due to water stress, and this leads to the production of sap (called kino), staining the trees ‘ginger’. Trees with ginger tree syndrome are expected to die within 12 months of the gingerness being visible. In the north-east of the state, ginger tree syndrome has been responsible for mass deaths of Eucalyptus viminalis, following a heatwave in 2013. Eucalyptus viminalis forest in the north-east has continued to decline in the last decade due to ginger tree syndrome.

Following the dry and hot Summer of 2021-2022, we went to check out a few sites of the viminalis trees in the Henty Dunes. Thankfully most trees were looking quite healthy, but a handful had very obvious signs of ginger tree syndrome.

Figure 4. Ginger tree syndrome on Eucalyptus viminalis subsp. hentyensis (Photos by Luke Cooper 2022)

Research on ginger tree syndrome is very new, and as far as I am aware there has been no study or records of the syndrome in the Henty Dunes. It isn’t clear if a similar number of trees had ginger tree syndrome in past years, or whether this is a new phenomenon following this dry and hot Summer. The trees on the dunes are exposed to the elements, with some even standing isolated in the sand. While they likely have adaptations to help them handle the harsh environment, they may not have adapted to withstand sustained hot and dry periods. This will be something to keep an eye on in the future.

On a Larger Scale: Ocean Beach Erosion

A recent paper from researchers at UTAS suggests that erosion on Ocean Beach, a 40km long Beach stretching from Macquarie Heads to Trial Harbour, is displaying an early response to climate change induced sea level rise. While this is more related to rising average global temperatures, not local climate activity, I will still mention it here as it has real and visible effects on the West Coast environment.

The paper used the aerial photo history of Ocean Beach to show that around 1980 the shoreline shifted from a stable state to a receding one. This means that since 1980 the shoreline of Ocean Beach has been moving east, towards land. This shoreline recession has shown no sign of stopping since 1980, and between 1980 and 2010, the shoreline has moved landward approximately 35 metres. During this time, the steep dune banks of Ocean Beach have been continuously eroding and exposing peat. Carbon-dating of samples of this exposed peat show that the current position of the shoreline has not been reached in at least the last 1800 years.

Figure 5: Erosion of the dunes on Ocean Beach. Large sections of peat are exposed. (Photo by Luke Cooper 2021)

The level of erosion on Ocean Beach has altered the environment in the Ocean Beach Conservation Area, and will continue to do so if the shoreline recession does not stop. One such change is the damage to shearwater (mutton bird) rookeries. The vegetated dunes bordering Ocean Beach are the seasonal homes to short-tailed shearwaters, and there are many substantial shearwater rookeries along the 40km beach. Some of these rookeries have already been affected by the erosion. For example, a small rookery right next to the visitor car park for Ocean Beach was completely destroyed in just a few days over the Winter of 2021 during a period of very high tides and strong winds.

While climate change effects such as ginger tree syndrome and erosion on Ocean Beach continue to be researched, it is difficult to envision solutions to these issues. It seems evident that these two phenomena will continue into the future, alongside increased fire frequency on the West Coast. In order to protect both people and high conservation value vegetation fire management in Tasmania needs to change, both in how bushfires are prevented and how they are controlled when they arise.

Ultimately, this requires state-wide commitment to adapting fire management and conservation techniques to protect a Tasmania with a changed climate. In the meantime, we can be informed on these issues, spread this information to others in our communities, and form strong, fact-based arguments for why change is needed.

Further Reading:

A video on Ginger Tree Syndrome in Tasmania’s North-East

Tasmania’s dry summer in review, as BOM eyes autumn with waning La Niña.